THE PHOENIX: Yeltsin and the Future of Russian Leadership

by

GWENDOLYN STEWART

originally published in the

Harvard International

Review, Volume XXI, Issue 1 (Winter 1999)

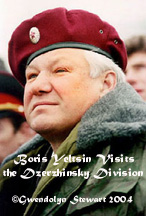

BORIS YELTSIN VISITS THE DZERZHINSKY DIVISION

In these troubled

times, an ailing Boris Yeltsin seems the almost too-perfect symbol for an

ailing Russia. This is not how the second term of the first Russian president

was supposed to turn out. Back in 1996, when the Communists under Gennady

Zyuganov appeared poised to take over the presidency (they had already won a

plurality in the Duma a half-year before), the ultimate rallying cry was

"Better a sick Yeltsin than a healthy Zyuganov." The Communists, it was

thought, could do positive harm; Yeltsin at least could hold the country

together as the fruits of market democracy ripened. Should worse come to

worst, there were constitutional provisions for choosing a successor now in

place; the Prime Minister, Viktor Chernomyrdin, would take over for three

months as acting president, and then elections would be called. There was also

already at least one other obvious candidate with a proven track record of

winning elections, Moscow's Mayor Yury Luzhkov. But the hope was that the

reinvigorated Yeltsin, who had toured Russia during the election campaign,

would move the country forward if given four more years.

# # #

GWENDOLYN STEWART is both a

photojournalist and a political scientist specializing in political

leadership in Russia, China, and the U.S.

A former Bunting (Radcliffe) Fellow, she is an Associate (and former

Post-DoctoralFellow) of the Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies

at Harvard, as well as an Associate in Research of the Harvard Fairbank

Center for Chinese Studies. For the Fairbank Center she

co-founded and co-chairs the China Current Events Workshop, a forum for

examining pressing issues in Greater China. Her Harvard

Ph.D. dissertation (SicTransit) dealt with the role of the

leaders of the republics, especially Boris Yeltsin, in the breakup of the

Soviet Union. She is currently writing

RUSSIA REDUX, the story of Russia under Yeltsin and Putin, part political

analysis, part travel-memoir: Imagine wandering over the largest

country on earth, not in the train of a railroad, but in the train of one

of the most powerful and contradictory men on earth. Or all by

yourself. COMMENTS?

PLEASE CONTACT:

Photograph by GWENDOLYN STEWART c. 2014. All Rights Reserved.

It seemed that important battles had been won, even if the

victories had been paid for at a bitter price. After the confrontation

with the Supreme Soviet had ended in the shelling of the White House, a

post-Soviet constitution had finally been hammered out and ratified by

popular referendum in December 1993. The main lines of development for

the new political system were clear: Russia was to be not a parliamentary

but a presidential republic too much so, it was almost certain. The war

in Chechnya, fought in the name of saving the Federation, had been brought

to an uneasy cease-fire with the prospect of an ending within sight. The

long-promised economic upturn had still not materialized, at least not in

the officially registered economy, but hyperinflation had been wrung out

of the system. Now it was time to show, in a fully contested election,

that Russians had moved beyond communism, away from their past, and were

still willing to bet on the future.

Then Boris Yeltsin failed to show up at his regular polling place

on July 3, 1996, the day of the crucial second and final round of the

election, but won with fifty-four percent of the votes anyway. Two months

later he made the unprecedented public announcement of his need for heart

surgery and on November 5, 1996, he underwent a quintuple bypass surgery.

The operation was declared a success, but the presidents health and the

political life of Russia have been on a roller coaster ride ever since.

The Making of Yeltsin

As obvious and devastating as the Russian crisis appears today, it

is necessary to place it in context, to reflect on how much has changed in

just a decade.

Ten years ago Boris Yeltsin was a failed Soviet politician,

drummed out of the ruling Politburo and passing the time in a make-work

job as deputy chief of the State Committee on Construction. Ten years ago

the Soviet Union was indisputably the other superpower, and the Reagan

administration had committed vast amounts of American resources in an

effort to close what it saw as a window of vulnerability to the Evil

Empire.

At home, the Soviet Union was entering the heady days of

democratization, centered on a new Congress of Peoples Deputies,

Gorbachevs attempt to give the country a meaningful albeit circumscribed

parliament. For the first time in more than 70 years something resembling

real elections were in prospect, and Boris Yeltsin seized his chance to

make a new, popularly-based political career. Andrei Sakharov, the

physicist turned dissident, made a fateful if somewhat reluctant decision

to ally with this former provincial apparatchik. He and the other liberal

Moscow deputies ran orientation sessions for like-minded incoming

deputies. Yeltsin was open to new opportunities and new programs after

his dismissal from Gorbachevs circle, and some of that orientation has

remained with him.

Originally from Sverdlovsk in the Urals, where Europe meets Asia,

the young Boris Yeltsin was athletic and smart. His peasant parents had

managed to finish only four years of school and some after-work literacy

classes between them; he did well to be graduated from the Ural

Polytechnic Institute as a civil engineer. Though Boris Yeltsin was a

beneficiary of the Soviet drive for industrialization, he made his career

not in the dominant military-industrial complex, but in a

consumer-oriented field. He ran a large city trust putting up pre-fab

housing blocks before switching over in his late thirties to straight

Party work. By the time he was 45, he was boss of his native province. He

was such a hard-charging type that he had already had an attack of heart

trouble severe enough to send him crashing to the floor a full decade

earlier. What a different career he might have had if there had been a

Rhodes scholarships for Russians!

The same dedication and aggressive commitment to work had brought

him to the attention of the Center when Mikhail Gorbachev was looking for

perestroika-worthy leaders. In December 1985, Yeltsin was appointed First

Secretary of Moscow. After less than two years in this high visibility

post in the capital, he made the first of several outsized gambles that

were to mark the rest of his career. At the Central Committee Plenum

called to prepare for the celebration of the seventieth anniversary of the

October Revolution, Yeltsin rose to complain about the slow pace of

perestroika, and offered his own resignation. In response, the Party

fired him. By volunteering to give up power in the name of reform, Yeltsin

became a martyr for many. He became first the peoples tribune and then the

president of Russia. But he paid an enormous price for this break with

his past, physically and psychologically.

In May 1990, Yeltsin was elected to the highest post in Russia,

Chair of the Supreme Soviet of the Russian Soviet Federated Socialist

Republic. Until the end of the Soviet Union barely more than a year and a

half later, Boris Yeltsin was engaged in a strangely interdependent dance

of statesmanship and gamesmanship with Mikhail Gorbachev, at times

antagonistically competitive and at times cooperative. The result was an

outcome that surprised nearly everyone: Russia peacefully let the empire

go. One major theme of the liberals with whom Yeltsin had allied himself

was the need to encourage real sovereignty for the constituent republics

of the USSR; Yeltsin made this his platform, engaging in bilateral

negotiations with the leaders of the other republics. In the end, with a

Russian taking the lead, the USSR was divided up without conflict.

Russia and Reform

If reforming the Soviet Union was never going to be easy,

reforming a rump Russia posed its own perils. Throughout the last seven

years, Russia has most often been in a state of what Aleksandr Lebed has

called shaky stability, punctuated by periodic upheavals. With economic

liberalization as their centerpiece, the Yeltsin reforms began immediately

after the breakup, but without the expected major stabilization fund from

the International Monetary Fund. The resultant hardships gave Speaker

Ruslan Khasbulatov and Vice-President Aleksandr Rutskoi an incentive to

oppose Yeltsin - a struggle which ended in the bloody October Events of

1993. A serious effort to contain hyperinflation was not made until after

the shock of Black Tuesday one year later. The stability hard won in the

economic sphere was undone in the war in Chechnya, which began in December

1994 and was not brought to a negotiated end until after the elections of

1996. Parliamentary elections in December 1993 and December 1995 afforded

opportunities for protest votes, bringing first the ultranationalist

Vladimir Zhirinovsky and then the Communists to prominence. The president

tacked in response to these outcomes, shedding deputy prime ministers and

ministers, even the foreign minister, as seemed necessary, but kept to his

own central course and balancing act. Throughout it all, he remained open

to criticism. His enemies were never silenced.

Yeltsin's domestic and foreign policies were linked. If political

liberalism had been the program of the reformers out of power in the USSR,

economic neoliberalism was the doctrine of choice in the West as Yeltsin

was coming to power. After watching Gorbachev flounder so long, unable to

make a clear choice for fundamental economic reform, Yeltsin boldly pinned

his hopes on the dominant wisdom of the day. Until the default and

devaluation of August 17, 1998, the Washington consensus maintained its

hold on his administrations approach to the economy, despite its zigzags

and corruption. Ironically, it was to be the Russian crisis, compounding

the Asian ones, which began to open cracks in the global monetarist

consensus.

The original Gaidar government had started out smartly trying to

break the stranglehold of the military-industrial-complex on the economy,

and the quest for partnership with the United States in particular

dictated an initial foreign policy that made Russian nationalists accuse

Yeltsin of taking orders from the Americans. President George Bush,

however, saw his country as having more will than wallet in 1992 and, in

an election year, not even much will to truly embrace the fledgling

Russian democracy as an ally. Nevertheless, he was keen to lock in

nuclear arms cuts, and did achieve the signing of SALT II just before he

left office. As the global political order changed to Russia's

disadvantage, the parliament saw the mandated reductions as a threat to

what remained of their country's military might, and balked.

This reluctance was part of a larger change, as the early earnest

openness and idealism about the possibilities of a post-Soviet Russia

faded, and the realities of the decline in Russias international position

set in. Arms sales abroad increased in importance as they proved to be

among the few industrial goods exportable to the global economy. Russia

came to be regarded as little more than a regional power.

The post-Soviet space itself was a source of knotty problems. Much

of the territory in what were now independent states had been part of

Russia's national identity for decades or even centuries. Yeltsin had

been in the vanguard in granting recognition to the other republics,

especially the Baltics, but the practicalities of working out the soft

divorce were perplexing. Russia was seen as a useful milk cow providing

subsidies, especially in energy supplies, but an arrogant Big Brother when

it expected special consideration in return. Russian forces did intervene

in the Commonwealth of Independent States in Tajikistan, Abkhazia and

elsewhere, but Russian troops withdrew from the Baltics as well as Eastern

Europe.

The End of a Presidency

How will the first Russian presidency end, short of the

president's death? The Constitutional Court has determined that Yeltsin

will not have a third term. But will he manage to hold on to his office

for the rest of his term, scheduled to end in mid-2000? With the

cooperation or connivance of some, most, or all of the Russian political

elite, he might just manage it. Or he could instead resign ahead of time,

more or less voluntarily; he could be impeached; or he could be forced out

on medical grounds. But then how will his successor be chosen? By

popular elections, as ordered by the Constitution? Or by a Constitutional

Assembly or some other elite electoral college mechanism, presumably

heavily weighted with parliamentarians? Not surprisingly, the speakers of

both houses of the Federal Assembly and the leader of the largest fraction

in the parliament, the Communists, find this latter approach very

attractive. Elections cost too much money, they say, and just happen to

be less likely to favor them. Finally there are the darker scenarios,

mostly centered on coups of one sort or another. There seem to be four

possibilities: soft resignation, resignation, removal for medical

disability, and impeachment.

The situation in Russia today can more or less be described as

soft resignation. The president is openly portrayed as a figurehead by

Russia media. In this scenario, Boris Yeltsin stays in office and shows up

for summits, even if they sometimes have to be held in the hospital.

Officially, the president is still even planning for further summits

abroad. This has some merit as long as there is a chance of recovery:

Yeltsin's past track record as the other Comeback Kid has some nervously

looking over their shoulders even now to see if he can pull it off yet

again. On December 7, 1998, he suddenly came out of the hospital and into

the Kremlin long enough to sack several of his own top aides, including

his chief of staff, Valentin Yumashev. Nominally designed to energize the

fight against corruption and political extremism(anti-Semitism and

communist restoration), this dramatic gesture aimed to demonstrate that

the president was still in charge. He did manage to get himself discharged

from the hospital after this bout of pneumonia, but as recurrent illnesses

succeed one another so closely as to qualify as chronic and apparently

debilitating, the option of hanging on for eighteen more months becomes

progressively harder to sustain. The question becomes whether having this

president in place, in this condition, is less destabilizing than an overt

vacancy and concomitant struggle for power.

In Yevgeny Primakov, the Foreign Minister turned Prime Minister,

the system has at least thrown up a plausible placeholder, and one with

whom other world leaders are already familiar. There are potential

drawbacks to the present situation, however, especially when authoritative

decisions are called for. Although several of the presidents subordinates

have announced that many of the presidents powers are being ceded to the

prime minister, and the presidents occasional appearances on television

subliminally convey the message of his removal from hands-on work, there

is still an air of impermanence to the arrangement. It is not the same as

maintaining General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev at the top of the Communist

Party of the Soviet Union and trusting that no one would dare to question

his authority.

Foreign affairs, which were the presidents special province and

enthusiasm, have become especially tricky. Yeltsin recently failed to

attend a banquet given in the honor of a visiting Japanese delegation, one

of whose members announced that their missing host looked like a robot.

The new German Chancellor, Gerhard Schroeder, disinclined to imitate his

predecessors concentration on his relationship with his Russian summit

partner, allowed himself to sneer at sauna politics. Jiang Zemin was not

so publicly gauche, but the Chinese were said to be studiously attempting

to divine which leader would rule in the post-Yeltsin era. In the end, a

visibly ailing president just makes Russia look weak and diminished in the

eyes of the other powers, almost the last thing the country needs at the

moment.

Given the severity of the current situation, it is possible that

Yeltsin will be induced to resign by a combination of threats(impeachment)

and inducements (his own golden parachute). The Russians call the latter

providing social guarantees, and the possibility of such being offered has

been bruited about for some time now. Most likely such a package would

include a pension, a dacha, bodyguards, and a promise of no prosecution,

including immunity for his family. One variation has Yeltsin, like

Pinochet, being made a Senator for life to insure the freedom from

prosecution, a promise perhaps somewhat devalued now.

Yeltsin's health may yet provide a pretext for forcing him from

office. Article 92, Section 2 of the Russian Constitution declares that

the president ceases the exercise of his powers early in the event of his

resignation, persistent inability to exercise his powers for health

reasons, or removal from office. What qualifies as medical grounds for

removal, and who makes the judgment, are questions as yet undetermined,

but now moving toward a possible resolution. The Constitutional Court has

agreed to meet on January 15, 1999, to take up these issues. To increase

the pressure in the meantime, the Duma on December 2, 1998, passed

anon-binding resolution demanding a report on Yeltsins health. The

attempt to counter accusations of persistent medical disability by putting

the president on television in the condition in which he has been seen

recently seems rather more likely to convince the public of the opposite.

But an exit on medical grounds would probably not suit the dignity of the

president and his family.

Finally, it is possible that Yeltsin will simply be impeached.

Duma impeachment commission hearings have been underway for some time and

are scheduled to be completed by years end. Five counts have been under

consideration and three have already been approved by the commission:

signing the Soviet Union away in Belovezhskaya Pushcha in December 1991,

firing on the parliament in October 1993, and launching war in Chechnya in

December 1994. The other two charges, the deliberate destruction of the

Russian military and genocide against the Russian people, are not so

likely to be carried forward to the Duma itself. Impeachment itself is

difficult, designedly so. The president is supposed to be removed from

office on charges only of treason or other grave crimes, and two thirds of

both houses of parliament and both the Supreme Court and the

Constitutional Court must concur in the verdict. Impeachment may not

actually be necessary to drive the president from office. The threat of

it may suffice, especially when combined with positive inducements.

If these are the main means available, the other part of the

puzzle is the timing. Officially, the presidents term is to last until

mid-2000; any early departure triggers a three-month acting presidency for

the prime minister, with a requirement for elections to be held at the end

of the period. There seems to be a palpable disinclination to rush the

date, with motives ranging from waiting for better weather or economic

conditions to a wish to push through some means of picking the president

that avoid a popular vote. Intertwined with the question in the minds of

some politicians is the upcoming election of the Duma in December 1999.

One option that has been put on the table by Aleksandr Shokhin, the head

of the generally pro-government Our Home Is Russia faction in the Duma, is

simultaneous early elections in September 1999 for both the president and

the parliament. So far, this option does not seem to have been met with

widespread enthusiasm. With no discernible consensus having yet

coalesced, and with Yeltsins reputation for obstinacy acting as a residual

deterrent, the presidential side has floated its own counter-offers,

including talk that the president will now concentrate on constitutional

reforms, including even the re-institution of the vice-presidency.

Primakov as vice-president could presumably guarantee the remainder of the

allotted term, and not just three months. One way or another, change is

coming.

Russia after Yeltsin

Trying to predict the next president of Russia a year and a half

out is at least as problematic as trying to do the same for the United

States. But there is now something of a stable of presidential hopefuls,

and, as we have seen, the election may come sooner than mid-2000.

Yevgeny Primakov, the Prime Minister and frequent stand-in for the

president, is still enjoying something of a honeymoon, often topping

political trust-and-popularity polls. But he disclaims any interest in

running for president, using his advancing age as an excuse. Keeping any

such ambitions hidden is also useful in diverting the wrath of the

incumbent as well as would-be competitors onto himself. He has yet to

announce a real economic plan, contenting himself with platitudes about

building a socially-oriented market economy with the participation of the

state. After such a prolonged depression in Russian industrial

production, perhaps he is danger of presiding over another bout of

hyperinflation.

Yury Luzhkov is the Moscow boss Boris Yeltsin would have liked to

have been. He made the capital into a showcase investment magnet; that is

both his glory and his burden. The rest of the country has a love-hate

relationship with Moscow, and his middle-class base suffered badly in the

August crash. But his good boss image resonates in the populace, and he

has attempted to build up a nationalist base outside the capital. He even

flirted briefly with an alliance with the Communists. Asserting Russian

rights in Crimea, now part of Ukraine, may win votes at home, but risks

destabilizing the neighborhood. An air of uncertainty also surrounds his

criticism of the privatization deals made under the Yeltsin administration

but outside of his aegis; might he try to undo some of them? Still, there

is a noticeable bandwagon effect in his favor. Even former prime minister

Viktor Chernomyrdin, whose own standing has declined so sharply, has

spoken of joining forces with him.

Aleksandr Lebed promises a firm hand with a vengeance. The former

general positions himself as the anti-corruption outsider, but seems to

have no stable political orientation. His brief stint as national

security adviser was his only civilian government post. He is finally

getting political executive experience, having been elected governor of

Krasnoyarsk Krai this past spring; whether he will make a success of the

endeavor is still an open question. He prides himself on his

independence, and his unpredictability worries the Russian political

establishment. But there are rumors that famed oligarch Boris Berezovsky

helped fund his campaign. And sometimes he is suspected by Russians of

being the American candidate, or at least, the American favorite.

Even though he has already lost once in a head-to-head race with

Boris Yeltsin, Gennady Zyuganov has to be counted among the contenders.

Somewhere between 20 and 30 percent of the populace identify with the

communists: the organizational base Zyuganov commands (the

half-million-strong Communist Party of the Russian Federation) is easily

the largest in the country, and he leads the largest fraction in the Duma.

However, he is not without challenges from within his own party, and not

just from the more radical, less electable extremists. The Communist

Speaker of the Duma, Gennady Seleznov, is talking about running for

president himself. Having the Duma vote to reinstall the statue of Iron

Feliks Dzerzhinsky, the founder of the Cheka-KGB, is either a gamble that

the crisis will ultimately radicalize the population, or a response to the

party base, or both. The impeachment process is in their hands.

Grigory Yavlinsky is trying to capitalize on an anti-corruption

crusade as well, but from the side of the clean democrat. He has never

met an offer from the Yeltsin administration that he thought worthy of

bringing him from opposition to active participation in running the

country. He did come in fourth in the last presidential election, and his

Yabloko party is one of only four to break the five percent barrier and

win a place in the Duma. The party is said to be increasing its

organizational base in the country, and Yavlinsky himself is the

top-ranking democrat/reformer in the polls, former Nizhny-Novgorod

governor Boris Nemtsov having dropped precipitously after his service in

the national government.

Coming in fifth in 1996 visibly deflated the clown prince of

ultranationalism, Vladimir Zhirinovsky, and he seems to be casting about

for other possibilities. He has talked of offering himself as somebody

else's prime minister, and even of running for a governors seat. But he

still commands one of the four parties in the Duma, and occupies his

special niche on the Russian political scene, even after wholesale

poaching on the nationalist front by other contenders.

So far, in spite of trial balloons about presidential selection by

other than popular ballot, the main focus of the political class does seem

to be fixed firmly on the forthcoming elections to both the parliament and

the presidency. Ten years ago, any sort of real elections was barely more

than a glimmer in Mikhail Gorbachevs plans for democratization. Now, a

set of distinctly post-Soviet political institutions, however imperfect or

warped, is in place. It remains to be seen whether the present economic

crisis can finally break the legendary patience and the spectacular coping

mechanisms of the Russian people.

"THE PHOENIX" in HARVARD INTERNATIONAL REVIEW, Volume XXI, Issue 1 ("PERSPECTIVES")

* * * *

An exhibition of a quarter-century of the photography

of Gwendolyn Stewart entitled "HERE BE GIANTS" was held at

Harvard.

Coming: HERE BE GIANTS the book.

* * * *

MORE ABOUT THE AUTHOR

BILL & BORIS & VLADIMIR &

GEORGE & Strobe Talbott's THE RUSSIA HAND: AMERICA'S RUSSIA POLICY

THOMAS P. O'NEILL, JR. (TIP O'NEILL)

FREDERICK SALVUCCI & THE BIG DIG

GAO XINGJIAN: CHINA'S FIRST NOBEL LAUREATE IN LITERATURE

© Copyright 2014 Gwendolyn Stewart. All rights reserved.