RUSSIA REDUX

by

CHAPTER ONE

PIVOT

"Those who were counting on this being the last congress and on the burial of the CPSU taking place at it have again miscalculated. The Soviet Communist Party lives and will live." -- Mikhail Gorbachev at the Twenty-Eighth and Last Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), July 13, 1990

IT WAS the Party's last hurrah. In the Soviet Union, even in the summer of 1990, there was no need to ask, "Which Party?" There was only one; only one that counted, anyway, and barely more than that at all. It was the Party's last hurrah, but almost no one in the Party could believe it. Four thousand, six hundred eighty-three delegates were summoned to Moscow. From eleven time zones and fifteen republics of the USSR they headed for the Palace of Congresses in the Kremlin. Drawn by power and by perks, they came, they argued, they networked, they postured, they partied, they preened. They cheered some of their bosses; they jeered others. Sometimes they cheered and jeered the same person.

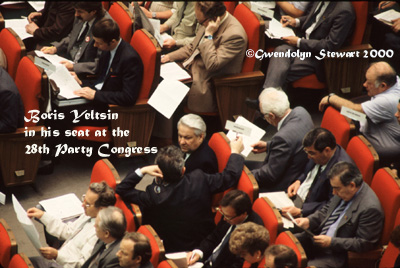

Four thousand, six hundred eighty-three delegates were called to the Twenty-Eighth Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, but only one walked out of the Congress, out of the Palace of Congresses, and out of the Party forever. That one was Boris Yeltsin. A handful of journalists were waiting in the foyer as he passed through, and I was one of them.

The long day was winding down into night, and the long Congress was winding down into the history books. It was July 12, 1990, the next-to-last day of a contentious two-week convocation of the leaders of the Soviet Union, the mighty and the small. It was evening outside and a bit dull inside the lobby of the great Palace of Congresses.

"Palace" very likely conjures up the wrong image. It is not Versailles; it is not the Hermitage, the former Winter Palace, in St. Petersburg. The Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., that "Kleenex Box on the Potomac," is more like it, another modernist construction built on government orders. The Palace of Congresses was the Soviets' chief public contribution to the Kremlin grounds, the last new edifice added on their watch to this ancient citadel. An ugly duckling -- no match at all for the ochre Italianate government buildings otherwise nestling within the Kremlin walls, to say nothing of the glory of the cathedrals, the buildings dedicated to God. And a threat to the rest of the Kremlin complex it was too. For in driving their five-story Palace fifteen meters underground, the builders had disturbed the foundations of the nearby older structures. A challenge it had been, to construct a grand gathering place for the People's representatives, to give a proper size and splendor to this chosen venue for the most authoritative meetings in the USSR, while keeping it from overshadowing its neighbors.

The Palace of Congresses lacks the Kennedy Center's dramatic setting on a hill above the Potomac. This is so even though the Kremlin also sits on a hill above a river, the Moskva or Moscow River. A much older invention, the Kremlin, unlike the Washington White House, is not one building, but a complex of buildings from different eras on a plot of land (sixty-nine acres of it) which is roughly a triangle, with a river side, a Red Square side and a city side proper. The Palace of Congresses is located on the city leg of the triangle, tucked behind the public entrance of the brick red Trinity Gate. Six days a week, then and now, the tourists, local and international, pour in through this gate, and for Swan Lake and New Year's celebrations and such the Palace itself (now rechristened the State Kremlin Palace) becomes a people's palace.

This plain box does at least have the saving grace of glass. If it cannot match the glories of its more fortunate older neighbors, it has one virtue not found in the Kennedy Center. It reflects the beauty of the gems of the Kremlin ensemble, capturing something of the cream and gold marvels nearby -- the Ivan the Great Bell Tower, the Assumption Cathedral -- in its light blue panels, knitted together by light marble pylons. This, as I had discovered on my first trip to the Soviet Union in 1984, is best captured by approaching not from the street side, but from the opposite side, from Cathedral Square. From this direction trees lend a cool, quiet dignity to the largely pedestrian oasis of this heart of power.

It was Nikita Khrushchev who had opened the Kremlin grounds to the public. In Joseph Stalin's time, the Kremlin had been a Forbidden City. And it was Nikita Khrushchev who had pushed through the construction of the Palace of Congresses in time for the Twenty-Second Congress in October 1961. To this Congress the thirty-year-old Mikhail Gorbachev had gone for the first time as a delegate; by then he had already been a member of the Party for nine years. Boris Yeltsin did not go. He had barely joined the Party, finally, in 1961 -- the same year in which, as it happens, he had also turned thirty. As Gorbachev was climbing up the Party ladder in his home province of Stavropol, Yeltsin was climbing another kind of ladder in Sverdlovsk, his native province. He too was becoming a boss. But he was building housing blocks instead of organizing political activity.

The Twenty-Second Congress was the second anti-Stalinist Congress Khrushchev conducted, the one he used to sanction removing the old dictator's body from the Lenin Mausoleum. Mikhail Gorbachev was there, and inspired by the reform spirit of Khrushchev's time. Boris Yeltsin was not. It was Gorbachev who had the vision and the drive to attempt to remake the communist system. Without Gorbachev, Yeltsin would most likely have remained only a provincial leader in an unreformed superpower muddling through to the end of the century. But it is Yeltsin who dreamed of going Khrushchev one better and removing Lenin himself from the Mausoleum, and of laying him to rest where he wished to be, next to his mother in St. Petersburg.

That Thursday night in July 1990, seven Congresses and nearly three decades after the construction of the Palace of Congresses, the delegates were tucked away in its vast (six-thousand-seat) auditorium, and most of the journalists on duty were in the hall with them. A few privileged Soviet correspondents strolled the long aisles of the auditorium; the foreigners and the rest of the Soviets with passes for the second half of the day perched up in the balcony, near the front, facing the dais from audience left.

Only a few of us kept vigil in the lobby, and a sprawling big multistory lobby it was; when it was empty it felt very empty. The walls and columns inside the Palace of Congresses were faced with marble and limestone "tufas" from around the Soviet Union, from Georgia, Armenia, Siberia, and the Urals. Pride of place in the foyer was given to the seals of the fifteen constituent republics of the USSR -- symbols of the fifteen republics that then but for not much longer comprised the Soviet Union. A hot topic of the summer was something called the Union Treaty. It was supposed to help bind the parts of the USSR together in a new cooperative relationship. Yet six of the fifteen had already declared themselves sovereign states, and three of the six had proclaimed their independence. Only on the lobby walls were they strung together in perpetuity.

My pool pass for the balcony having expired for the day, I was confined to the area outside the auditorium. I rode the escalator up and down to see who else was about, biding my time, knowing that the best opportunities for interviews and photographs came in bursts, during the breaks between sessions. Over several days at the Congress I had learned the drill. The old Soviet rules were gone. Even Communist Party bigwigs were fair game when they emerged from the hall.

CBS, I had discovered, was camped out in the foyer too. They had a TV monitor one flight up from the main entrance to the auditorium, and they were keeping watch on the proceedings. I drifted up to check out what was happening officially, and drifted back down in case any delegates ventured out betweentimes. And up again.

Suddenly a rush! Boris Yeltsin had unexpectedly interrupted the proceedings to ask to speak, and to the astonishment of the auditorium, had announced his resignation from the Party. As head of the Russian Republic, he said, he could not continue to be subjected to the directives of any party. The father of the country he was to be, above the fray, above any parties. I flew downstairs to station myself by the door to await his exit.

It had taken Yeltsin a month and a half after he had become "president" of Russia, or what was then known as the Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic (RSFSR), to fulfill his campaign pledge to resign from the Party if he did. So difficult was it for him to break this tie that he even had considered suspending his membership rather than giving it up altogether. Anguished days and sleepless nights preceded his decision. Being a president without a party has its penalties. He has done without the organization and the connections, even though periodically he suggested that a presidential party should be formed. His heart did not seem to be in it. The experience with the CPSU seems to have made "party" a bad word for many Russians.

Already since his ascension to the top post in the RSFSR on May 29, 1990, Yeltsin had been accused of being dictated to by Democratic Russia, the movement that had helped him win election to the RSFSR parliament in the first place. Yet he had announced his resignation from Democratic Russia two days after being elected head of the Supreme Soviet, and its members complained that Yeltsin did not consult them or offer patronage to the very people who helped get him elected. So for him to keep his CPSU membership even temporarily was anomalous. On the other hand, he did not lay claim to the leadership of the Russian Communist Party when he was elected Chair of the RSFSR Supreme Soviet, even though Gorbachev had argued that Party and state functions could or should be combined at the local level, and he himself held both posts at the top level. Gorbachev was President of the USSR; Gorbachev was General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. Yeltsin was "advising" him to give up one post or the other, and supposedly setting him an example by not going after the top job in the Russian Communist Party. Never mind that it was extremely doubtful that Yeltsin had any chance at winning that post, as conservative as that new outfit was turning out to be.

Meanwhile, he had a state to run, more or less, a fragment of the Soviet Union. Quite a fragment: three quarters of its landmass and half its population. But what was it, this Russia, this RSFSR? Never had it been meant to take seriously its constitutionally enshrined prerogatives. The Party ruled. Everyone else took orders. Nonetheless, two weeks after barely winning the top Russian post in a vote in the Congress of People's Deputies, he had coaxed a symbolically ringing Declaration of Sovereignty out of it. He was reaching out to the leaders of the other Soviet republics, even -- or especially -- those in revolt against the first Moscow, the Moscow of Mikhail Gorbachev. But their positions were, if anything, more precarious than his. No other republic had anywhere near the weight of Russia. To make his mark, should Yeltsin stand constantly in opposition? Or should he seek instead a direct collaboration with the Center, with Gorbachev -- where the power was?

He had waited to see what the CPSU would do at its Congress. It had, after all, been his party for almost three decades. This was perhaps the last chance to reform the system on something like a Union-wide basis, through the Party. The capture of the Russian Communist Party by Ivan Polozkov  and the other conservatives on the eve of the CPSU Congress bode ill for such a possibility. "Neanderthal" was a label that the combination of Polozkov's physiognomy and anti-market rhetoric conjured up for Russians all too easily. The members of what was now "his" Russian Communist Party made up more than half of the membership of the all-Union Party, and the delegates to the just-completed Russian Party Congress were carried over directly as delegates to the Twenty-Eighth Congress itself. There was talk, some of it by Yeltsin, of the need to postpone this long-awaited, "extraordinary" (ahead-of-schedule) CPSU Congress, of putting it off until another, better day. Gorbachev kept his nerve, and opened the Congress on July 2nd, as planned.

and the other conservatives on the eve of the CPSU Congress bode ill for such a possibility. "Neanderthal" was a label that the combination of Polozkov's physiognomy and anti-market rhetoric conjured up for Russians all too easily. The members of what was now "his" Russian Communist Party made up more than half of the membership of the all-Union Party, and the delegates to the just-completed Russian Party Congress were carried over directly as delegates to the Twenty-Eighth Congress itself. There was talk, some of it by Yeltsin, of the need to postpone this long-awaited, "extraordinary" (ahead-of-schedule) CPSU Congress, of putting it off until another, better day. Gorbachev kept his nerve, and opened the Congress on July 2nd, as planned.

Ten days later, with only one day left to go, Gorbachev could be forgiven for feeling self-congratulatory. For all the threatened revolts from right and left, he had held his Party together. He had managed to steer the Congress through to some sort of middle course. For Yeltsin it was not enough. He quit; now he would be president of all the citizens of Russia and not of only one party. As it was nearing its end, he decided that "there would be no renewal in the party." So:

"When they began to nominate people for the Central Committee and my name appeared on the lists, I understood that the time had come to make a statement about my decision to withdraw from the CPSU. The atmosphere was extremely tense and two-thirds of the 5,000 people in the hall were feeling negative, but I did not respond to the "booing" because everything was very serious by now. I spoke after having thought everything over beforehand, but when I descended from the podium I felt that the eyes of the people in the hall were following me: Would I go back to my seat or leave? I left, and I think that put an end to it."

Although he had telegraphed his intentions during the election campaign, the Congress collectively was stunned by his announcement. After all, he had just been proposed for membership in its Central Committee. After all the fuss he had caused and the grief he had given them, the Party still wanted him. Or at least, Mikhail Gorbachev was willing to have him sit among the four hundred or so top rulers of the CPSU. The Politburo, the inner body, was a different matter. Membership in the Politburo was not on offer. But then the Politburo was no longer to be what it had been, either; it was losing its most favored position.

Quitting the CPSU was not a simple matter. One did not casually hand back one's Party card. For all his agonizing, Boris Yeltsin was willing to cut himself off from the mother lode of power and community in the Soviet Union. Not that he was the first Party member to do so -- 136,600 of the eighteen-plus million on the rolls of the CPSU had done so in 1989, and another 82,000 in the first three months of 1990, it was reported at the Congress. But he was certainly the first at his level. "Shame!" "Shame!" rang out in the auditorium as he departed.

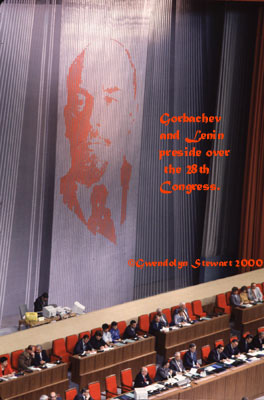

Gorbachev, presiding over the Congress, had been the one to give Yeltsin the floor when Yeltsin had sought recognition to speak, and Gorbachev had had the dubious pleasure of sitting directly behind Yeltsin when his former lieutenant made his short but shocking farewell address. For all that he was master in this realm, Gorbachev seems to have been shaken by the news.

There he sat, bang in the center of the ruling dais. A mammoth multistory red head and shoulders of Lenin painted on gray accordion-fold drapes hovered behind him. His almost-peers, men who were comrades from the Politburo or leaders of the communist parties of the Soviet republics, spread out to his right and left on the dais. Behind them sat the supporting row of staff, and on the third of the three tiers, a daring if small array of telecommunications and computer equipment on a stray table. Gorbachev was used to the Palace of Congresses, and used to presiding in it. When he had invented the Congress of People's Deputies, the new super-parliament, it too, like the Party Congresses, was allotted these very same premises for its sessions. Mikhail Gorbachev conjured up these new gatherings, and Mikhail Gorbachev presided over them.

There he sat, lord of the realm twice over: President and General Secretary, General Secretary and President. And there, directly in front of him, at the wide podium, with his back to his President and his General Secretary, Boris Yeltsin revealed that he was jumping ship: "...I announce my departure from the CPSU," he said. They were nominating him to a ruling position in an organization he no longer wished to be a member of at all. Gorbachev grasped the nettle. He declared that it hardly made sense to enter Boris Yeltsin's nomination to the Central Committee, and he called on the Congress delegates to cancel his mandate to the Congress itself. Immediately. It would not even be necessary, he declared, for Yeltsin to have to go to his primary party organization (the old Party cell) to hand in his Party card.

In his memoirs, Gorbachev gives a cool account of his own reaction. When Yeltsin pulled this stunt he decided, he writes, "to treat this question as a routine matter...." He watched "Yeltsin's ostentatious exit from the conference hall. He walked slowly, probably thinking that the delegates would applaud and someone would follow him." No one did. One eyewitness describes Gorbachev as having sat "impassively" while Yeltsin spoke, and delivering his own remarks afterwards with "a wry smile." But as Yeltsin made his long walk out of the hall, another heard "a flushed and angry" Gorbachev snap "into a microphone he thought was dead: 'Can't you see how I feel? Leave me alone.'"

In coming to cover the Congress, I had brought my opinion of Yeltsin with me from the States. While studying for a Ph.D. in Political Science at Harvard, I was back to taking photographs on assignment for Business Week, as I had for a number of years in Washington.

Kohl wanted a unified Germany as his legacy. Gorbachev's attempts at economic reforms had now reduced the Soviet Union to sending urgent emissaries to plead for funds. The Bush administration was willing to supply the currency of words. NATO's London Declaration of July 6th that the Cold War was over was thought a master stroke to help Gorbachev. But it was followed immediately by the Houston G-7 summit in which George Bush refused the request for a substantial (twenty-billion-ish) assistance package. Bonn decided it would provide three billion dollars of credit on its own. As my seatmate on the press bus into the Kremlin, NBC's diplomatic correspondent John Dancy, succinctly put it to me, "They're buying East Germany." But would Gorbachev be able to sell the "bargain" to his own people?

The fall of Eastern Europe was not some abstract concept for the Kremlin, especially in the summer of 1990, eight months after the Berlin Wall had come down. It was fodder for Congress delegates berating the leadership for what it had already lost. "New Thinking" had freed the East European regimes to manage on their own, only to have them to wind up being overthrown. Yeltsin had used his big speech to the Congress the first week to warn the Party that the fate of the "fraternal" East European parties might be its fate, its leaders dragged from power and brought to trial. He had called for pluralism in the Party, in one last attempt to get his old Party to reform, to revitalize itself, and to take the symbolic leap to embrace Democratic Socialism in its name, as well as in its platform. He failed; he left.

In the short run, Boris Yeltsin's dramatic gesture hardly seemed to carry all before it. The newly elected mayors of Moscow and Leningrad, Gavriil Popov and Anatoly Sobchak, did announce their resignations from the Party -- in absentia, at a press conference of their representatives the day after Yeltsin's departure. The Democratic Platform, with which Yeltsin had been aligned, quarreled within itself whether to go or stay. When Yeltsin abandoned the effort for reform from within, he did not put himself at the head of an alternative party, but rather concentrated on building on the state structures at hand in the Russian Republic.

Boris Yeltsin had designed his resignation from the Party for maximum showmanship. At the risk of alienating his own parliament, he had decided to wave his declaration of independence right in the face of the leader of the Party he was discarding. But his farewell address included no direct, slashing criticism of that Party. He flamboyantly signaled his unique importance without insulting Gorbachev beyond forgiveness. Gorbachev responded to the gesture and the reality of Yeltsin's newly won position as head of Russia by inviting him in for their first long, substantive talk in many months. The two agreed to join forces. They put together a team to hammer out what came to be known as the 500 Days program, as Gorbachev moved to accommodate the restless Soviet republics in a new economic deal. Yeltsin left on a tour of his new domain, and I unexpectedly found myself observing him in action again. I was about to be educated -- to learn what Boris Yeltsin meant to Russians, from Russians.

Chapter Two: THE PEOPLE'S CHOICE: Yeltsin on Sakhalin

MOSCOW & the GULF WAR: Excerpt from Chapter Three

* * * *

An exhibition of a quarter-century of the photography of Gwendolyn Stewart entitled "HERE BE GIANTS" was held at Harvard.

Coming: HERE BE GIANTS The Book.

* * * *

GWENDOLYN STEWART is both a photojournalist and a political scientist specializing in political leadership in Russia, China, and the U.S. A former Bunting/Radcliffe Fellow, she is an Associate (and former Post-Doctoral Fellow) of the Davis Center for Russian and Central Eurasian Studies at Harvard, as well as an Associate in Research of the Harvard Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies. For the Fairbank Center she co-founded and co-chairs the China Current Events Workshop, a forum for examining pressing issues in Greater China. Her Harvard Ph.D. dissertation (Sic Transit) dealt with the role of the leaders of the republics, especially Boris Yeltsin, in the breakup of the Soviet Union. She is currently writing RUSSIA REDUX, the story of Russia under Yeltsin and Putin, part political analysis, part travel-memoir: Imagine wandering over the largest country on earth, not in the train of a railroad, but in the train of one of the most powerful and contradictory men on earth. Or all by yourself.

BORIS YELTSIN'S MIDNIGHT DIARIES

BILL & BORIS & VLADIMIR & GEORGE & Strobe Talbott's THE RUSSIA HAND: AMERICA'S RUSSIA POLICY

THE PHOENIX: YELTSIN & THE FUTURE OF RUSSIAN LEADERSHIP

THOMAS P. O'NEILL, JR. (TIP O'NEILL)

FREDERICK SALVUCCI & THE BIG DIG

GAO XINGJIAN: CHINA'S FIRST NOBEL LAUREATE IN LITERATURE

© Copyright 2024 Gwendolyn Stewart. All Rights Reserved.